A recent book on the Swansea Canal, its internationally significant early railways and the role they played in developing the global industries of Swansea and the Swansea valley has been recognised by being given two prestigious UK national awards.

The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (UK) and the Swansea Canal Society have published Arteries of Sustainable Industry: The Swansea Canal and its Early Railways by Stephen Hughes, former Secretary-general of the international industrial archaeology group TICCIH. This is an archaeological and historical study of the Swansea region: one of the earliest intensive industrial landscapes in the modern world. At its centre was athe Swansea Canal and its public railway system authorised by an Act of Parliament in 1794.

This integrated transport system enabled the development of the world centre of a series of international industries – copper, tinplate, iron, coal and early railway development. Some of the first public railways were planned for early locomotives, engineers involved built tunnels from the 1760s and iron railway bridges from the 1780s. As noted by the great canal historian Charles Hadfield it was at Gwauncaegurwen, on the western fringes of the Swansea Valley, that the first underground mining canal was tunnelled in 1757. In 1774 a mile long underground canal was driven into the hillside under what is now Morriston by the Lockwood, Morris & Co. Forest Copperworks at Swansea.

The canal engineer James Cockshutt reintroduced Roman techniques of waterproofing waterways. Cockshutt was the former managing director of what was developing into the largest ironworks in the world at Cyfarthfa, Merthyr Tydfil.

(Image: Stephen Hughes)

(Image: Stephen Hughes)

Joshua Gilpin, an American industrial reporter or ‘spy’ reported on meeting the Swansea Canal engineers at Swansea in 1796 who explained how they were using hydraulic (Aberthaw) lime rather than cumbersome clay to waterproof the aqueducts, wharves and locks of the new waterway. This was 5 years before Thomas Telford completed and claimed his use of hydraulic lime to waterproof the sides of the Chirk Aqueduct was the first use of this material for that purpose.

The international background of a multipurpose waterway unique in Britain is explored. It was unique in the extent that it provided a water-power resource attracting new industry that also used the water for transport and processing. The local gifted engineer, George Martin, originally from Whitehaven saw an opportunity. In 1810 he built a large cornmill on the canal banks (at Trebannws) to use the waste canal water flowing into the River Tawe above the intake of the two large coppermill complexes on the river. During the construction of the Swansea Canal the intended top two locks of the canal were never built but the large head feeder to the canal from the River Tawe was constructed at its earlier intended high level. In 1824 this available water resource prompted the construction of the first ironworks (Aber-craf) to attempt to smelt iron with hard anthracite coal rather than softer bituminous coal as previously used.

Continued experiments at nearby Ynyscedwyn Ironworks in 1837 were successful in applying hot blast to the anthracite iron process using blast water-wheel powered blast, partly using waste-water from the canal conveyed along a navigable canal branch. This breakthrough had profound implications for the growth of the anthracite-fuelled iron industry both in the UK and the USA. In the Swansea Valley it led to the construction of a single line of 11 blast-furnaces built into the side of the Swansea Canal at Ystalyfera, possibly the largest single line of such structures at the time.

Two of the earliest tinplate works (Pheasant Bush & Primrose), established in 1839 and 1844, by two brothers at what became the world centre of the industry also used the by-wash or bypass waters of two sets of twin locks.

The Swansea-based Cambrian newspaper was the first to publish the successful run of the Penydarren-built Trevithick locomotive in 1804. In the same newspaper the engineer/entrepreneur Edward Martin announced that because of the successful run of the locomotive the seven miles Oystermouth Canal scheme around Swansea Bay was to be changed to a railway construction. This was the first railway to be designed for steam locomotive operation. The Oystermouth Railway Act specially allowed for the use of locomotives rather than horses but Trevithick chose to concentrate on other schemes rather than his proposed lighter locomotive that could have run on the Oystermouth line’s brittle cast-iron plateway track.

On opening the Oystermouth Canal was a commercial failure. One of the redundant limestone wagons was adapted to run the world’s first timetabled public railway passenger service. Timber-framed river ferry buildings at Swansea formed the first railway station to be established internationally.

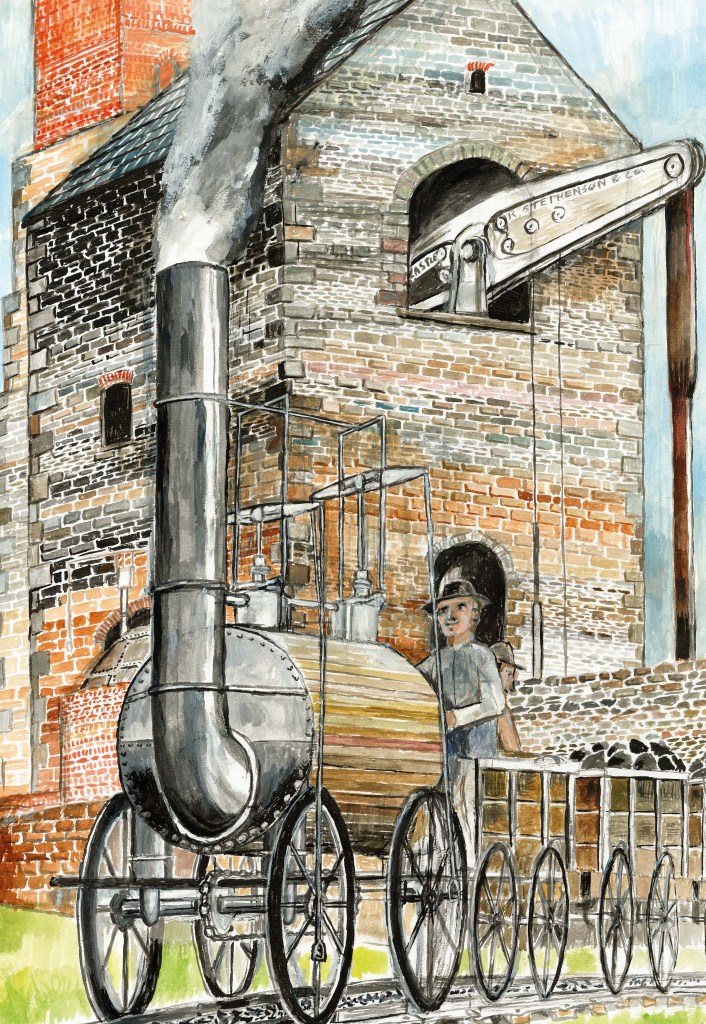

The third independent railway to be built in the lower Swansea Valley was the three mile long Scott’s Coal Pit Railway engineered by Roger Hopkins. It was the first new line to be run using a steam locomotive from its completion in 1818. Its railway line to the Swansea Canal over the Beaufort Bridge Viaduct was a public railway designed to use an early Stephenson locomotive, one of the first two to be operated outside the Newcastle Coalfield. George Stephenson and Nicholas Wood were both present at the opening.

The international development of canal & early railway use is explored in detail in two of the four chapters. The book can be purchased for online at www.ebay.com & www.swanseacanalsociety.com/swansea-canal-book-sales and the 82 reconstructions painted by the author for the book can be seen at www.Etsy.com/shop/BuildingsofWalesArt and www.canaljunction.com .